The sun-scorched plains of the Ethiopian highlands have known the whisper of the wind for millennia. It is a constant companion, rustling through the dry grasses, sweeping across the Great Rift Valley, a silent, powerful force that has shaped the land and its people. For generations, this wind was simply a fact of life, the breath of the earth. But today, this ancient zephyr carries a new promise, a modern covenant. It is no longer just a natural phenomenon; it is the key to unlocking a future of light, industry, and sovereignty. As the global community, as detailed in the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) Report 2025, navigates the turbulent currents of record growth and persistent challenges, Africa stands at the precipice of an energy revolution, with Ethiopia poised to become a central character in this transformative narrative.

A Global Gale and Africa’s Faint Breeze

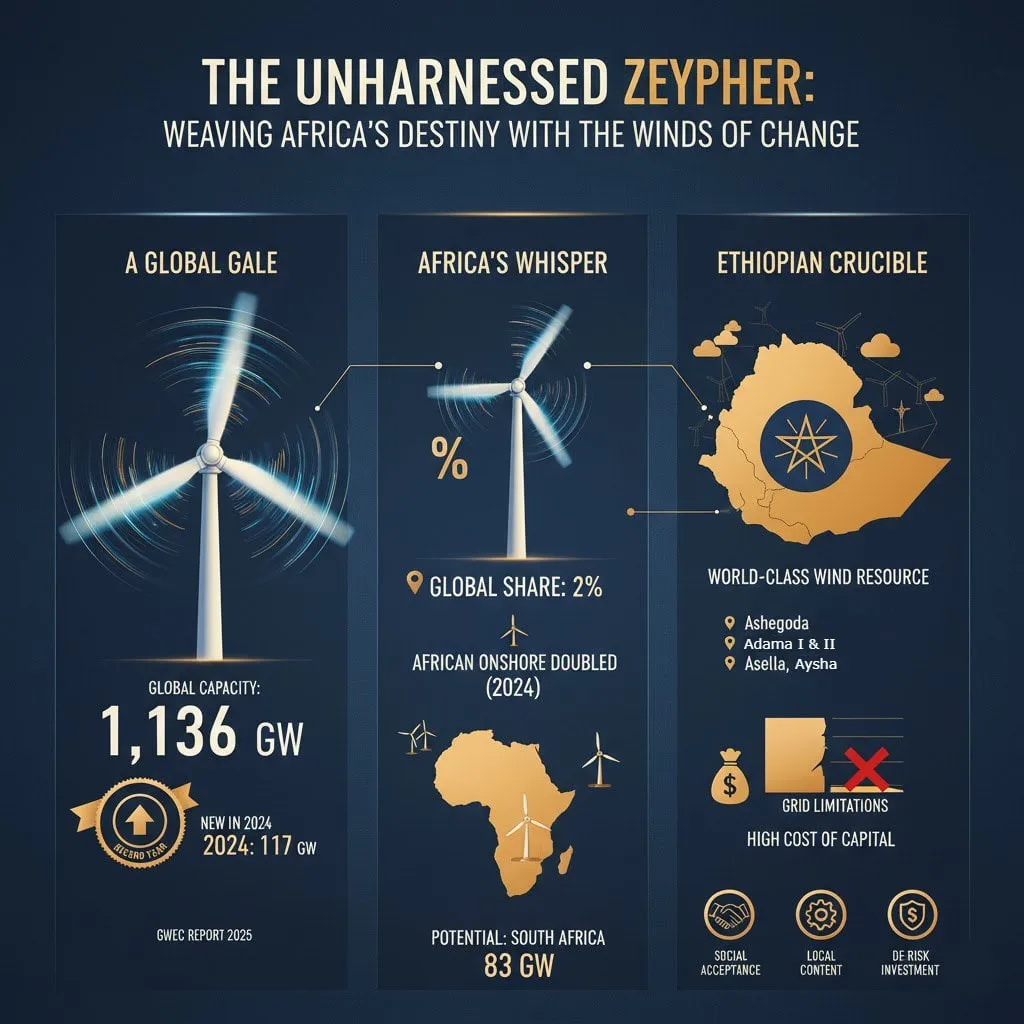

The world is in the midst of a wind energy renaissance. The GWEC report heralds 2024 as another record year, with 117 GW of new wind capacity spinning to life across the globe, bringing the world’s total to a staggering 1,136 GW. This is a story of human ingenuity, of harnessing an invisible force to power our civilizations. Yet, within this triumphant global chorus, Africa’s voice remains a faint, though strengthening, and whisper. The continent, alongside the Middle East, remains the smallest market, contributing a mere 2% to the global total of new installations in 2024.

But to focus solely on this percentage is to miss the crescendo building beneath the surface. This was the year Africa’s onshore wind additions doubled. In Egypt and Morocco, turbines rose against the desert sky, symbols of a nascent industrial awakening. South Africa, a long-standing leader on the continent, continues to navigate its complex energy transition, with a project pipeline identified by the South African Renewable Energy Grid Survey (SARECIS) reaching a breathtaking 83 GW. The ambition is there, etched into national plans and the determined faces of engineers and policymakers. The potential is as vast as the Sahel, as boundless as the Saharan horizon. The question is no longer if Africa will harness its wind, but how fast and how wisely it will do so.

The Ethiopian Crucible: Potential Forged in Challenge

Imagine the gusts that sweep from the Danakil Depression to the Simien Mountains. Ethiopia’s wind resource is not merely good; it is world-class. The same winds that have carved its dramatic landscapes can now carve its economic destiny. The country already boasts landmark projects like the Ashegoda, Adama I and II, Asella and Aisha wind farms, concrete testaments to what is possible. They are not just power generators; they are beacons, illuminating a path forward.

Yet, the path is strewn with obstacles familiar to emerging markets, echoes of the very challenges detailed in the GWEC report. The most formidable of these is the grid. Like a fragile web, Ethiopia’s transmission infrastructure struggles to carry the full potential of what the wind offers. The report’s global diagnosis of grid congestion as a “critical barrier” resonates deeply here. A turbine standing idle for lack of a connection is a monument to missed opportunity. Furthermore, the financial headwinds are stiff. The high cost of capital, a recurring theme in the GWEC analysis for emerging economies, makes the substantial upfront investment in wind projects a daunting prospect. Investors, wary of perceived risks, demand higher returns, creating a financial Catch-22 that can stall progress before a single foundation is laid.

Lessons from the Global Playbook

The GWEC report is not just a catalog of achievements and problems; it is a repository of solutions, a global playbook from which Africa and Ethiopia can draw critical lessons. The first lesson is on de-risking investment. The international community has developed a toolkit green bonds, concessional financing, credit guarantees precisely for markets like these.

By leveraging these instruments, Ethiopia can lower the financial barriers and attract the patient, long-term capital that wind energy requires. It is about creating a stable, predictable environment where investors see not just risk, but unparalleled reward.

The second lesson is the imperative of industrialization and local content. The global race for larger turbine platforms is a double-edged sword, but within it lies an opportunity. Ethiopia does not need to manufacture 20 MW turbine giants overnight. But it can, and should, build a local ecosystem. This means training a workforce welder, electricians, technicians, data analysts. It means developing local capacity for tower fabrication, component assembly, and maintenance. The GWEC report warns against inflexible Local Content Requirements (LCRs) that drive up costs, but it also champions the “bedrock of the energy transition” through local skills and supply chain integration. The goal is not isolationist protectionism, but smart, strategic localization that creates jobs, retains value, and builds a resilient national industry.

The third, and perhaps most profound lesson, is the battle for social acceptance. The GWEC report dedicates significant attention to the “orchestrated disinformation campaigns financed by fossil fuel interest groups.” While the context may differ, the principle of community engagement is universal. A wind project cannot be an alien structure imposed upon a landscape; it must become a part of the community’s fabric. This means transparent communication from the outset. It means designing benefit-sharing schemes where communities co-own projects, where local schools and clinics see direct improvements, where the wind farm is not just a source of power for distant cities, but a source of pride and prosperity for its immediate neighbors. It is about humanizing the technology, telling the story of the local father who found skilled work, the child who studies under electric light for the first time.

A Vision Woven from Wind

For Ethiopia, and for Africa, the energy transition is about more than megawatts and carbon reduction. It is the cornerstone of a new form of sovereignty. For too long, the continent’s economic narrative has been tied to the extraction and export of raw resources, leaving it vulnerable to volatile global commodity markets. Wind energy flips this script. The wind is a domestic resource. It cannot be embargoed; its price cannot be manipulated by a cartel. It offers energy independence, a shield against the geopolitical storms that so often buffet developing economies.

By embracing wind power, Ethiopia can power its own industries, from textile manufacturing to tech hubs, with clean, affordable, and reliable electricity. It can become a regional energy hub, exporting power to neighboring nations and fostering regional integration and stability. The vision extends beyond the grid. The GWEC report speaks of “power-to-X” solutions using renewable electricity to produce green hydrogen for fertilizer or to power clean transportation. Imagine Ethiopian agriculture revitalized by locally produced green ammonia, or cities where buses run silently on fuel created from water and air. This is not a distant fantasy; it is the logical endpoint of a committed energy strategy.

The winds of change are blowing. They are blowing across the North Sea, where massive turbines stand sentinel, and across the plains of Inner Mongolia. But they are also blowing across the Horn of Africa, carrying the dust of ancient history and the seeds of a boundless future. The GWEC Global Wind Report 2025 serves as both a mirror and a map. It reflects a world grappling with its own success, and it charts a course forward. For Ethiopia, the map is clear. The challenges of grid infrastructure, financing, and community engagement are real, but they are not insurmountable. They are the crucible in which a green industrial giant can be forged.